Optimising Training and Racing Around Your Menstrual Cycle

Most women will experience symptoms related to the menstrual cycle at some stage in their life, and many of these symptoms can your impact capacity to train and race, as well as your ability to adapt to and recover from different types of training sessions.

The menstrual cycle is often seen as an annoyance or hinderance (for very understandable reasons). However, in the context of training, it can also be extremely useful in terms of providing a marker of health and sufficient fuelling, as well as providing a monthly boost in performance and training capacity.

In this article, we’ll explain how and why female hormones can affect training and performance, how you can help reduce some of the negative symptoms, and importantly, how you can plan your training to work with your menstrual cycle and capitalise on phases where you have the biggest capacity to train, perform and adapt. We’ll also look at how hormonal contraceptives might interact with training.

Every woman is different, so bear in mind that we’re generally describing ‘typical’ or ‘common’ experiences. We acknowledge that these may not be felt by all, but nevertheless, we think most women can still take something away from this article by having an improved understanding of how female hormones can interact with training.

What happens through the cycle?

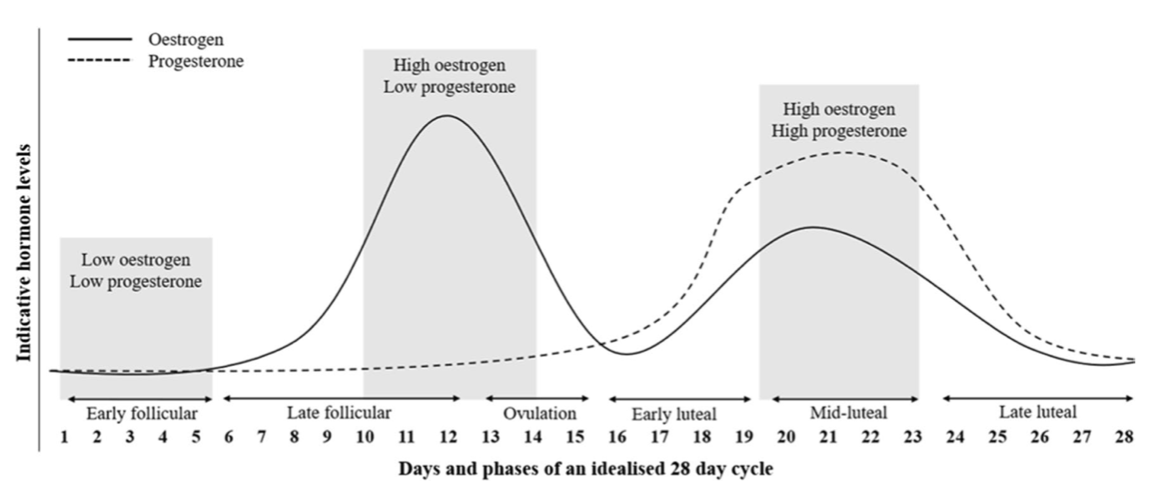

The menstrual cycle starts on the first day of your period, and finishes on the day before your next period. In women who have a regular cycle (see below), and who are not taking hormonal contraceptives, the menstrual cycle can last between 21 and 40 days, but is typically around 28 days. The cycle can be broadly divided into three key phases: follicular, ovulation and luteal, as illustrated in the diagram below, which is taken from McNulty et al. (2020).

The follicular phase begins on the first day of bleeding and ends around 14 days later at the point of ovulation. The main hormones present through this phase are:

follicular stimulating hormone (FSH), which is produced by the pituitary gland and sends a message to the ovaries to prepare an egg for release.

oestrogen, which is produced by a dominant follicle in the ovaries. Levels of oestrogen increase as the follicle grows and an egg is prepared for release, with the level of oestrogen peaking just before ovulation. Increasing oestrogen levels send a message to the uterus to rebuild the uterus lining after bleeding, and to prepare the uterus for a potential pregnancy.

luteinizing hormone (LH), is produced by the pituitary gland right at the end of the follicular phase, in response to very high levels of oestrogen. This triggers the release of the mature egg and begins ovulation.

The ovulation phase lasts around 24 hours, during which time the egg travels from the ovaries and down the fallopian tube, towards the uterus. If the egg is not fertilised within 12-24 hours of release, it dissolves. Otherwise it continues to travel down the fallopian tube. Levels of oestrogen drop during ovulation.

The luteal phase is concerned with creating conditions within the uterus to support a pregnancy, should one occur. During this phase, the follicle that contained the newly-released egg now produces both progesterone and oestrogen. The progesterone tells the uterus to stop thickening and to prepare to receive an egg.

The levels of progestogen and oestrogen peak around the middle of the luteal phase, after which point the follicle begins to break down and the levels of these hormones fall, which helps to trigger the next period.

The uterus also releases chemicals, such as prostaglandins, which help support early pregnancy. The levels of these chemicals rise during the luteal phase, and peak during the period. Prostaglandins have been linked with a range of menstrual symptoms, as we will cover in the next section.

The three main phases can also be divided into sub-phases, based on the levels of female hormones, and can be summarised as:

Early follicular: all hormones are at relatively low levels. Prostaglandins are high.

Late follicular: oestrogen and LH are high

Early luteal: progesterone and oestrogen are rising.

Mid-luteal: progesterone and oestrogen are high.

Late-luteal: progesterone and oestrogen are falling. Prostaglandins are rising.

In each of these phases, you can have quite different menstrual symptoms, and abilities to train, perform and adapt, due to the different hormonal profiles.

Irregular cycle and amenorrhoea

Before describing the impact of female hormones on training and performance, it’s worth speaking briefly about irregular cycles.

An irregular cycle is when the length of time between your periods varies considerably from cycle to cycle. For example, one month it might be 35 days, and the next it might be 26 days. In extreme cases, you may miss periods entirely. If you miss three or more periods in a row, this is known as ‘amenorrhea’.

There can be a wide range of reasons for irregular or missed period, including stress, pregnancy, contraceptive use and stage of life, with irregular/missed periods being more common in early puberty and just before the menopause. Progesterone only contraceptives commonly give rise to irregular periods, or can stop these entirely.

However, if none of these factors are present, then the regularity of your menstrual cycle can be an extremely useful marker of health, and in particular, a key indicator for whether you’re taking in enough energy (i.e. calories) to fuel your training alongside your regular bodily functions.

When energy intake is chronically low, this can trigger the body to go into an energy conservation mode, where reproductive processes (i.e. the menstrual cycle) are suppressed, and this manifests in irregular periods and/or amenorrhea. Having chronically low energy intake to the point that your menstrual cycle is impacted is known as Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S), and is a syndrome that’s tied with a whole host of negative health implications, such as impaired bone density, cardiovascular health, and impaired immunity, to name a few. It’s also associated with low mood, increased risk of injury and impaired performance and adaptation to training.

The prevalence of under-fuelling among female cyclists is notably higher than for the general population. The ability to be able to track your periods and make sure these are occurring regularly is therefore an extremely useful tool. Noticing changes in the regularity of your menstrual cycle can act as an early warning sign to consider whether your fuelling may be an issue and address this if so.

Impact of female hormones on training and performance

The two main hormones that interact with training capacity and performance are oestrogen and progestogen.

Oestrogen can be broadly seen as supportive of training and performance. It’s associated with a wide range of physiological changes, including improved vasodilation (i.e. blood flow), increased muscle glycogen storage, reduced muscle catabolism (i.e. less muscle break-down), improved neuroexcitability (i.e. ability to activate muscle fibres), increased fat-burning and glycogen-sparing (Lebrun et al., 2013; McNulty et al., 2020).

In contrast, progestogen is somewhat negative for training and performance. It promotes catabolism (muscle break-down), impairs fat oxidation ability, and increases body temperature, which has down-stream effects on things like the onset of sweating, skin blood flow, and haemoglobin disassociation, as well as sleep quality and general recovery (Lebrun et al., 2013; McNulty et al., 2020).

Both hormones also seem to impact fluid retention and sodium handling, as well as neural control of breathing and carbon dioxide handling (Lebrun et al., 2013).

Prostaglandins (the chemicals released by the uterus during the luteal and early follicular phases) are also linked with many of the commonly-known menstrual symptoms, such as cramps, headaches and bowl disturbances that can occur during the period, and which can have indirect effects on the ability to train and perform.

What this means in practical terms?

While it’s good to have a general understanding of how the female hormones can affect your physiology, the ultimate impact of these hormones and chemicals can be complicated, as they interact together. It’s therefore easier to talk in terms of phases of the menstrual cycle, rather than impacts of specific hormones in isolation. The key points are summarised in the table below, but we’ll also walk through each of the phases in turn.

PMS: Premenstrual Syndrome.

Early Follicular Phase

If you suffer from heavy bleeding, this phase might cause practical obstacles that make training hard (e.g. in terms of your ability or confidence in completing longer training sessions). You might also experience common symptoms of premenstrual syndrome (PMS) such as cramping, back pain, headaches, nausea or diarrhoea, due to high levels of prostaglandins, which can impact your mental or physical ability to train.

While the quality of evidence is currently very low, there is some indication from a recent meta-analysis, that women’s performance might be lower on average during the early follicular phase, compared with all other phases (McNulty et al., 2020). This study pooled data from 51 studies, and included a mixture of aerobic and anaerobic performance measures. As an average, the magnitude of the performance impairment was very small, and potentially trivial. However, there is probably a subset of women who experience more extreme PMS symptoms, and for whom performance is impaired by a more sizeable amount.

In contrast, women who have very minimal PMS symptoms during menstruation may feel relatively strong and able to train and compete well during the early follicular phase. As the levels of female hormones are low during this phase, then this can, in principle, be a time of the month where you can tolerate high training loads, and a mixture of different session types (i.e. both high and low intensities and strength training).

Women with more severe PMS symptoms can look to methods of alleviating these as much as possible, so that they feel better able to train. It’s worth noting that if you experience cramping, exercise has actually been shown to be more effective in pain reduction than over-the-counter pain medication (Armour et al., 2019). Table 1 of this article includes a summary of the evidence supporting different complimentary therapies for PMS symptoms.

If your symptoms are particularly severe, then you might need to look to medication. Ibuprofen can reduce prostaglandin levels and lighten menstrual bleeding by around 25% in women with heavy periods (Rodriguez et al., 2019), but there are side effects, such as risk of kidney disease and stomach ulcers from long-term use. Alternative medical solutions include tranexamic acid (Bonnar et al., 1997), or Naproxen (Davies et al., 1981), which might be even more effective at reducing bleeding. You should consult with a GP before considering these meditations.

Irrespective of the severity of PMS symptoms, it may be wise to take an iron supplement during your period to help reduce the risk of developing anemia and to help the body more effectively replace the red blood cells that have been lost (Rehrer et al., 2017). A reduction in red blood cells will acutely lead to a reduction in VO2max.

Bottom Line: experiment with different strategies for alleviating any menstrual symptoms. If you can alleviate these symptoms, then in principle, this should be a phase where you have good responsiveness to training and ability to perform.

Late Follicular Phase

In this phase, oestrogen levels are gradually increasing, which leads to improved fat oxidation, and glycogen storage and improved muscle building abilities. Overall, you will generally be feeling strong, and should recover quite quickly between training sessions, so this is a good time to incorporate higher training loads.

Be aware that oestrogen does reduce your ability to utilise internal stores of carbohydrates, in the form of glycogen. So you might need to make sure you’re fuelling with carbohydrates during any intensive training sessions (e.g. at or above your threshold power). You’ll usually want to aim for 1-2g/kg of body weight of carbohydrates between 1-3 hours before an intensive session and between 30-60g per hour of carbohydrates during the session. Provided you attend to this, then overall, this is a very good phase for most types of training.

Bottom Line: this is the best time of the month for training and performance, and we’d recommend capitalising on your higher training and recovery capacity by planning a higher training load than normal. High-intensity training will likely benefit from increased carbohydrate intake before and during.

Ovulation & Early Luteal Phase

Through these two phases, you should have a fairly average capacity to train and perform, because the levels of female hormones are lower, and you will not normally be experiencing any symptoms of PMS (although in some women these can begin in the early luteal phase). Through these phases your hormonal profile is more similar to that of a male, and you can follow non-gendered training guidance through these phases (which is usually derived from research in males!).

Bottom Line: In general, we’d recommend training ‘normally’ through these phases, without needing to make any special adjustments for the menstrual cycle.

Mid Luteal Phase

In the mid-luteal phase, both oestrogen and progestogen are high, and this I can have a notable negative impact on training and performance. In particular:

You may notice you have a higher heart rate, breathing rate, and perceived effort level for a given power output in this phase (Lebrun et al., 2013).

There is some evidence your first and second lactate thresholds may be slightly lowered (Lebrun et al., 2013)

You will likely have difficulty utilising stored muscle and liver glycogen, which can make longer and/or high-intensity sessions feel harder (Lebrun et al., 2013)

High progesterone levels can increase muscle catabolism (i.e. break-down), which can make recovery take longer and make muscle-building harder.

Core body temperature is increased, which can lead to sleep disturbances, and impaired recovery, and can also increase the risk of overheating during exercise (Lebrun et al., 2013).

Asthma symptoms can be exacerbated.

Thirst, sodium regulation, and fluid retention are all altered during this phase, which can increase the risk of developing hyponatraemia during prolonged exercise (a potentially dangerous condition where serum sodium concentration falls very low) (Rehrer et al., 2017)

In addition to these direct effects on training and performance, you may also begin to experience some symptoms of PMS through this phase. In particular, mood disturbances can be quite common in the mid-luteal phase (Yonkers et al., 2008).

Despite these many negative factors, a recent meta-analysis that pooled data from 78 studies was unable to detect a statistically significant performance decline during the mid-luteal phase (Lebrun et al., 2013). However the reviewed studies were generally of poor quality, with small sample sizes and a range of methodological issues (68% of studies rates ‘very low quality’). There is ample anecdotal evidence that women do at least perceive to have a performance decline through this phase, and we believe it’s worth taking some steps to help counteract these negative factors. In particular:

If possible, aim to align your recovery weeks with the mid-luteal phase of your cycle, so that the volume and amount of intensive training you’re aiming to achieve is less demanding.

If you do need to perform at a high level through this phase (e.g. you have an important competition), then focus on fuelling well with carbohydrates before and during the event, so that blood glucose levels remain high. This will help to counteract the suppressed ability to use stored muscle glycogen. For important competitions aim for 2-4g of carbohydrates per kg of body weight 2-4-hours before your competition and then 60-90g/hour of carbohydrates during.

For other training sessions, then supplementing with some carbohydrates (e.g. 30-60g/hour) may also be advisable. This may help reduce the perceived effort level, and there is also some evidence that this can help counteract the catabolic effects of progesterone (Rehrer et al., 2017).

Increase your protein intake above 1.6g/kg body weight per day, which will also help reduce muscle break-down.

Counter-intuitively, this may be a good phase to compete in lower-intensity endurance events (e.g. long sportive or ultra-distance events) due to the improved ability to use fats for fuel.

Practice good sleep hygiene and try to keep your bedroom as cool as possible, choosing pyjamas and bed sheets that also help to keep you cool.

Take care to avoid over-drinking during prolonged exercise, and replace sodium losses with appropriate electrolyte drinks (Rehrer et al., 2017).

If you’re suffering from PMS symptoms, then check out the guidance above in relation to the early follicular phase to help address these.

Bottom Line: This is the time of the month where you’ll probably find training and competing feels hardest, so try to align this with a recovery week of possible. If that’s not possible, be sure to focus on fuelling well with carbohydrates and protein to support performance, reduce perceived effort and improve recovery. Take care not to over-drink when completing long training rides in the heat and supplement with electrolytes to reduce the risk of developing hyponatremia.

Late Luteal Phase

In principle, through this phase, as levels of oestrogen and progesterone fall, there should be an improvement in performance and training capacity. However, changing hormone levels can trigger PMS symptoms in many women, and these can negate any benefits from lowered hormone levels. In particular, mood disturbances usually peak in the late luteal phase (Yonkers et al., 2008).

For women who experience few PMS symptoms, or who are able to manage these through other methods (as described above) then this can be a phase where you should be able to tolerate more normal training loads. However, if PMS symptoms are severe, then you may need to plan or allow for somewhat lighter training through this phase.

Bottom Line: Minimise PMS symptoms as much as possible through medical or non-medical means in order to improve training and performance capacity.

Hormonal Contraceptives

There are a wide range of hormonal contraceptives available. Hormonal contraceptives can differ in the hormones included, with some including only progestin, and others a combination of progestin and oestrogen (‘progestin’ is a synthetic form of progestogen). They also differ in their strength, potency and ‘androgeneity’ (capability of the progestin to exert masculine characteristics), and in terms of how the doses of hormones are ‘phased’ throughout the cycle, in order to simulate the natural hormonal fluctuations experienced throughout the menstrual cycle. Thus, hormonal contraceptives can have quite a wide variety of physiological effects depending on which ones are used.

For some women, hormonal contraceptives can help to alleviate symptoms that can interfere with training and performance (such as heavy periods, cramps, and low mood). Many women also favour hormonal contraceptives such as the combined pill because they help with altering the timing at which bleeding occurs, which can be useful in timing bleeding so as not to coincide with important races, or training camps, for example.

However, while there can be many benefits of hormonal contraception, it’s worth considering whether these synthetic hormones might have an impact on training capacity or performance. At the moment, there is fairly limited research in this area.

The majority of research that does exist has been conducted on the combined oral contraceptive (commonly termed ‘the pill’). Some of the strongest evidence we have at the moment comes from a meta-analysis that pooled data from a number of studies into oral contraceptive use and markers of aerobic and anaerobic performance. Importantly, this study found that performance was impaired by oral contraceptive use (Elliott‑Sale et al., 2020).

It’s thought that this performance-impairment might be because the hormonal contraceptives down-regulate the production of endogenous oestrogen and progesterone. So through the whole cycle, the hormonal profile appears similar to the early follicular phase (Elliott‑Sale et al., 2018). This is true even if a pill-free week is taken, as there is insufficient time for endogenous hormone production to increase (Elliott‑Sale et al., 2020).

Some combined oral contraceptives have been found to impact things such as breathing rate, cardiac output, body temperature, substrate utilisation and glucose uptake, and may reduce aerobic capacity (Lebrun et al., 2013). They can also lead to increased body temperature, impacting a range of things such as the onset of sweating and skin blood flow (Reher et al., 2017). Studies also indicate that some oral contraceltives increase fluid retention, leading to weight gain and a potentially increased risk of hyponatremia in long events (Reher et al., 2017).

Another big disadvantage of using hormonal contraceptives is that it masks your regular cycle and the useful marker of health.

It’s worth noting though that in the meta-analysis mentioned above, the magnitude of the performance-impairment was found to be quite small overall, and there appears to be quite large variability in the responses between women. So ultimately an individualised approach needs to be taken. For example, in women who experience very severe PMS symptoms, the benefits of being able to train more consistently throughout their cycle might outweigh the potential negative implications. Indeed, a great number of athletes perceive hormonal contraceptives to provide a net benefit (Engseth et al., 2022).

To our knowledge, there is no data on the impact of hormonal contraceptives on the ability to adapt to training (i.e. whether training adaptations are suppressed or enhanced, for example). We also currently have very little data on other forms of hormonal contraception (e.g. the hormonal coil, the progestogen only pill, and the implant). It’s been suggested that forms of contraception such as the hormonal coil, that deliver a very low and targeted dose of progestin directly to the uterus might be the best type of hormonal contraceptive for athletes wanting to minimise potential negative impacts on performance. This is because this avoids systemic hormone circulation and doesn’t suppress endogenous oestrogen production (Sims, 2016). To our knowledge, there is no scientific evidence to support or refute this at present, but in theory, the logic makes sense!

Whatever you decide, you should always consult with a GP before taking any forms of hormonal contraception, and bear in mind that there can be wider health implications and side effects.

Conclusion

Hopefully the information above has provided some useful pointers to help you get the most out of your training through the different phases of your menstrual cycle. We’ve done our best to present the evidence as it currently stands, but bear in mind that research into the interaction between female hormones and training/performance is extremely limited, and often of low quality. So recommendations may change as the evidence improves. Also, please remember that we are not medical professionals and you should always consult with your GP if you are considering any medial form of intervention and/or have any concerns about your menstrual cycle.

Free Workout Guide

Get your Key Workouts Guide; a free collection of 10 highly-effective, fundamental workouts you can use today to begin improving your endurance, threshold power, VO2max and other vital cycling abilities.

References

Armour, M., Smith, C. A., Steel, K. A., & Macmillan, F. (2019). The effectiveness of self-care and lifestyle interventions in primary dysmenorrhea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC complementary and alternative medicine, 19(1), 1-16.

Bonnar, J., & Sheppard, B. L. (1997). Treatment of Menorrhagia during Menstruation: Randomized Controlled Trial of Ethamsylate, Mefenamic Acid, and Tranexamic Acid. Journal of Lower Genital Tract Disease, 1(4), 246-247.

Davies, A. J., Anderson, A. B., & Turnbull, A. C. (1981). Reduction by naproxen of excessive menstrual bleeding in women using intrauterine devices. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 57(1), 74-78.

Elliott-Sale, K. J., & Hicks, K. M. (2018). Hormonal-based contraception and the exercising female. In The Exercising Female (pp. 30-43). Routledge.

Elliott-Sale, K. J., McNulty, K. L., Ansdell, P., Goodall, S., Hicks, K. M., Thomas, K., ... & Dolan, E. (2020). The effects of oral contraceptives on exercise performance in women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Medicine, 50(10), 1785-1812.

Engseth, T. P. P., Andersson, E. P., Solli, G. S., Morseth, B., Thomassen, T. O., Noordhof, D. A., ... & Welde, B. (2022). Prevalence and self-perceived experiences with the use of hormonal contraceptives among competitive female endurance athletes in Norway: The FENDURA project. Frontiers in sports and active living, 142.

Lebrun, C. M., Joyce, S. M., & Constantini, N. W. (2013). Effects of female reproductive hormones on sports performance. In Endocrinology of physical activity and sport (pp. 281-322). Humana Press, Totowa, NJ.

McNulty, K. L., Elliott-Sale, K. J., Dolan, E., Swinton, P. A., Ansdell, P., Goodall, S., ... & Hicks, K. M. (2020). The effects of menstrual cycle phase on exercise performance in eumenorrheic women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Medicine, 50(10), 1813-1827.

Rehrer, N. J., McLay-Cooke, R. T., & Sims, S. T. (2017). Nutritional strategies and sex hormone interactions in women. In Sex hormones, exercise and women (pp. 87-112). Springer, Cham.

Rodriguez, M. B., Lethaby, A., & Farquhar, C. (2019). Non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (9).

Sims, S. T., & Yeager, S. (2016). Roar: how to match your food and fitness to your female physiology for optimum performance, great health, and a strong, lean body for life. Rodale.

Yonkers, K. A., O'Brien, P. S., & Eriksson, E. (2008). Premenstrual syndrome. The Lancet, 371(9619), 1200-1210.